Langar, Tajikistan

Life in the Wakhan Valley - Part I

May 25, 2012

Oh, I await the day

Good fortune comes our way

And we ride down the King's Highway

- Tom Petty

From Khorog, already isolated in its own right, a spur of road loops south to the Wakhan Valley where the Pamir River and Wakhan River merge to form the Pyanj (Oxus) River, creating a natural geographic border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The broad valley has long been a transit corridor through the mountainous region and Marco Polo even ventured through here on his travels. The views are spectacular with the giant jagged peaks of the Hindu Kush demarcating the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan visible to the south and the slightly smaller Pamir Mountains to the north. In between them is a winding river valley with its turquoise waters providing a lifeline for the many villages dotting its banks. With so many years of history the valley is littered with archeological remains, from ruined forts to ancient petroglyphs.

Traveling the 200 kilometers between Khorog and Langar to explore this remote and seldom visited region it often seemed as if life had changed very little in those thousands of years. The small villages still seem to survive on agriculture with all the work done by hand. Electricity is little and inconsistent, there is no internet, and most people wake with the sunrise and go to sleep soon after sunset. The only difference seems to be simplified communication via cell phones, which links the neighboring villages closer together. The lack of technology makes walking around very peaceful as the only sounds that can be heard are the rustling of the wind, the rushing of the river, and the occasional vehicle passing through. In fact there is really only organized transport two days a week so with limited transport it is difficult getting around and the villages seem to subsist on their own. In fact the most reliable form of transport is walking as some villages are separated by only five or ten kilometers.

Fortunately for me I was in a 4WD jeep making it much easier to see this isolation and peace and quiet that seemed to only enhance the beauty of the natural surroundings. Immediately after leaving Khorog the roads winds through amazing red rock canyons with gushing waterfalls from the still melting snow. Across the river the road on the Afghan side rides higher and steeper up the canyons, and though lacking in vehicle traffic is traveled more by donkeys and other livestock along with their herders in traditional Afghan robes. Further down the road on a small hill in the valley past Ishkashim are the ruins of Khaakha Fortress from the 3rd century BC. It’s builders had a keen eye for the strategic location and part of the fort is currently used by the Tajik military to guard this section of the Afghan border.

My driver seemed to know the area very well, which he should after driving here for forty years and living in Langar for the last ten. In the afternoon he stopped at every few villages to go into these tiny village stores, often there would be only one in each village. Walking into these places was like traveling back in time. It wasn’t so much the things on the shelves, though there could have been canned goods from the Cold War, but it was the way items were arranged, crammed randomly together on crooked handmade wooden shelves with fading paint that gave them this timeless impression. They also sell many things by weight yet still use a traditional balance so that you can only buy things in ¼ kg increments, because those are the only counterweights they have. Several also had abacuses next to the checkout desk, though these were all replaced by calculators for even the simplest mathematical operations, leaving doubts as to the education levels of the store proprietors. In these stores the driver would get shots of vodka and some type of small snack like sliced cucumbers with salt or peanuts to chase it with. I joined him for two of these rounds and it was unbelievably cheap with the total coming to less than a dollar for the two of us before it was time to get back on the road.

And the road itself was amazing, at times climbing up high above the valley floor with grand views of herders driving their animals across the wide river plain. After descending back to the valley floor we reached the turn off for the ruins of the Yamchun Fort, dating from the 12th century and perched on the top of a bluff at 500 meters above the river. Looking past the fort you could see for miles in each direction, up and down the valley. Just after the fort at the end of this steep dirt road was the Bibi Fatima hot springs, the most interesting hot springs I have visited. From the edge of a steep river canyon there is hot water of a perfect temperature pouring out of broken stalactites in virtual waterfalls, the water having hollowed out tiny side pools and structures in the rock. The area is enclosed, creating a nice buffer from the cool mountain air that still provides some relief from the hot water.

Not further past this, on the Afghan side of the river are the ruins of the Qala-i-Panja fort, which used to be one of the larger villages in the valley. Maybe 50 kilometers ahead, near Langar, the Wakhan and Pamir Rivers split, the former heading into Afghanistan and even more remoteness, the latter forming the Tajik-Afghan border. With this strategic location there are two other ruined forts, the more dramatic of the two being the Ratm Fort, perched on the edge of a sheer cliff above a rushing river, it has been guarding the valley since the 2nd or 3rd century BC. The ruins of the fort overlook the valley floor far below and the peaks of the Hindu Kush in the distance to the south.

Langar is one of the larger villages in the region, although it is still small. The sight of foreign cyclists riding through such a town at mid-day creates quite a distraction. Walking back from the fort I passed two French cyclists who had biked all the way from France over the last year and were on their way to Kyrgyzstan and beyond. It was strange to see other foreign tourists in such an isolated place but then only thirty minutes later I met two Dutch cyclists, Rick and Judi, who were riding parts of the Silk Road starting from Uzbekistan. They ended up staying in Langar as well so I was fortunate enough to have some company in visiting the local sights and in the short but uneventful evenings such a small town provides, otherwise I think it would have been rather dull there.

While not providing much in the form of entertainment, there is at least a school in Langar and during the days I passed several children on their way home from school dressed much more formally than the surroundings warranted. They go to school for about 3-4 hours a day so at least there is some form of education in the valley, although where that can take them is rather unclear. That Friday in the valley was graduation day for the schools so along the road I walked stride for stride with children dressed up in their suits and dresses for the graduation ceremonies. For everyone else it was a day for celebration and drinking. I was invited to join some men for a beer at a village store. The beer turned into a picnic outside the store with shots of cognac at 10am followed by some grilled chicken before I managed to break away. For those actually finishing school I hope there will be opportunities for them but I think, for better or worse, they will revert to what they end up doing in the afternoons, when after school lets out the children can be seen working the land, riding donkeys, herding animals, and carrying water to the houses and fields. With few other options it seems they may be destined to becoming better educated farmers, carrying on the traditions of the region.

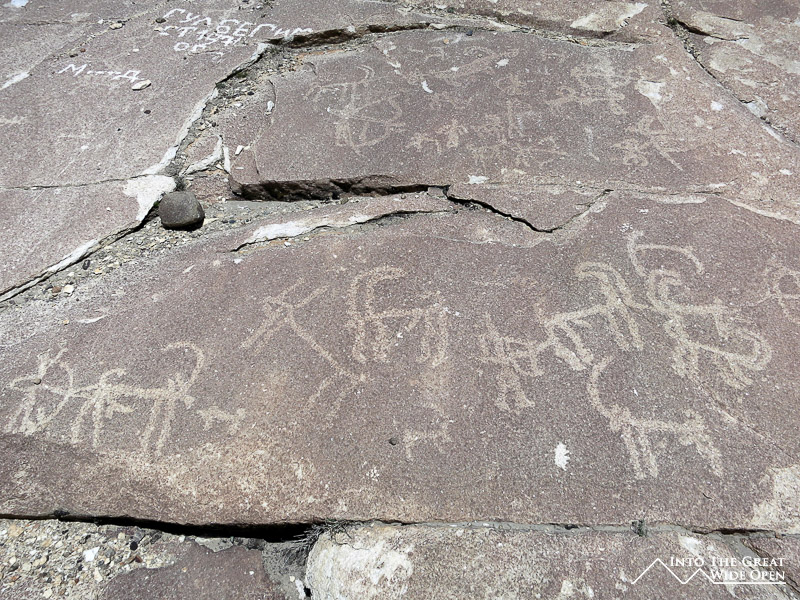

The earliest of these regional traditions can be seen in the thousands of petroglyphs on the rock faces high above Langar. Reached by scrambling up the steep slopes the petroglyphs depict hunting of Marco Polo sheep and ibex with bow and arrow, as the early explorers used to do. Today the animals are still hunted with the skulls and horns adorning the local Ismaili shrines as decorative elements, illustrating the indelible link between the past and present in this timeless region.