Potosi, Bolivia

The Mines and Another Strike

June 4, 2008

I get up at seven, yeah

And I go to work at nine

I got no time for living

Yes, I'm working all the time

It seems to me I could live my life

A lot better than I think I am

I guess that's why they call me

They call me the working man

- Rush

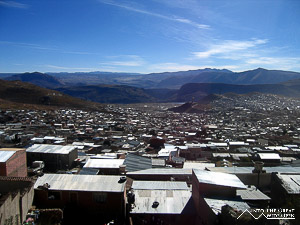

Officially, Potosi is one of the highest cities in the world with about 140,000 people at an elevation of over 4,000m. Although when I was in Peru I stayed in Cerro de Pasco, another mining city with 30,000 people at an altitude of 4,300m, so I suppose it depends on what you call a city. The city of Potosi is perched at the foot of Cerro Rico, the mountain where the mining takes places and materials such as tin, silver, and antimony are extracted. Other than the mines, a few churches, and a decent museum, there is little reason to visit Potosi. The mines are really the focal point of the city and tourists come to experience and marvel at the horrid conditions in which the miners work to support their families, something the miners are no doubt find confusing.

A tour to the mines begins by outfitting yourself with a jacket, pants, boots, and a helmet with lamp so that you don´t get your clothes covered in mine dust and your head is protected in the low and narrow tunnels of the mine. After this, they take you to the miner´s market where you have a chance to buy gifts for the miners like dynamite, coca leaves, potable alcohol, and soda. A bag consisting of one stick of Bolivian dynamite, a fuse, and highly explosive nitrates costs about $2. Because the miners work under such horrific conditions there is a lot of drinking and chewing of coca leaves to make it bearable. The miners drink something called potable alcohol because it is exactly that, drinkable alcohol, a solution of 96% alcohol made from sugar cane that burns all the way down.

The day I did the mine tour was one day after a holiday so most of the miners weren´t actually working and were loitering outside the mine drinking; there were only a few inside the mine working. The tunnel into the mine began easily enough with the roof high enough so that you could stand as you followed the railroad tracks into the mine. Our guide was a former mine worker who had started working in the mines at age 10 helping his father by running errands and doing random small tasks. By the time he was 12 he was helping with the heavier labor tasks. He told us that when you are born into a mining family you have no alternative but to inherit the work of your father and go into mining yourself. Your only recourse would be to learn English and become a tour guide for the mines, which is exactly what he had done. Some of the miners work for themselves and others work for the cooperatives where they have fixed schedules and earn money regardless of the amount of minerals that they find. Though the conditions are appalling, the money, relatively speaking, is pretty good, which is of course why they work and brave the hazards of the mine.

On the first level of the mines there is a small museum in one tunnel with information on the history of the mines and mining in Potosi. In another tunnel on the first level there is a statue of the God of the mines, with offerings placed around him. Most of the mining is done in the fourth and fifth levels of the mine, almost an hour’s scramble down from the entrance. The tours only take you down to the third level and in total you spend about 2-3 hours inside the mine, more than enough time for the acrid dust to burn your lungs and airways. Some of the miners work shifts of up to 24 hours in the cramped tunnels with terrible air quality. Even a few days after the tour of the mine the smell of the rock dust was still on my skin. The tour is definitely not for the claustrophobic as at times the passageways are so tight that you are crawling on your hands and knees to get through, all amidst the hot clouds of dust. One person in our group just couldn´t take it and was forced to leave after only 10 minutes or so. After our time underground we left the mines to have some fun with the dynamite. Our guides showed us how to unpack the dynamite and make a nice little bomb with the dynamite, the nitrates, and the fuse. They then lit the three minute fuse and let us each hold the bomb before scurrying off to put the bomb a safe distance away. A loud explosion from each bomb and a cloud of smoke erupted from the barren ground, shaking everything nearby.

The tour to the mine was certainly interesting, but at the same time depressing as after two hours below ground all of us were ready to get out into the fresh air. Knowing that the miners worked under those conditions for much longer hours, six days a week, you could only imagine the long list of respiratory and health problems that they rapidly develop. But as with all difficult jobs in the end it comes down to economics, the jobs pay well and the miners put up with the conditions because it is a means to support their families, although sadly there seems to be little socioeconomic advancement from one generation to the next, save for the few motivated enough to learn English and become tour guides.

As interesting as the mine tour was, Potosi as a city didn´t offer much of interest. There were a few nice looking churches, one with an intricately patterned facade, and one good museum, the Casa de Moneda. Visits to the museum are by guided tour only and you have to pay extra to take photos of the artifacts in the museum. There are rooms with random collections of things such as old coins, paintings, minerals, child mummies, minting machinery, and a really cool 30 foot long illustrated history of the world from the time of Adam and Eve up to the 1880s. After seeing the museum there wasn´t really anything else that I wanted to do in Potosi but I was trapped because of a nationwide road blockade resulting from the protests over a potential 200% increase to taxes on heavy transport and the poor quality of the roads. Supposedly the blockade was only set to last for 48 hours but a group of us decided, especially after waking up in the morning to a citywide power outage, that we would try our best to get out of Potosi despite the blockade.

The six of us called two taxis and when they arrived we told them we wanted to go to Sucre if the drivers could get us across the blockade line. On the way to the blockade line our taxi driver was on the radio to the main office asking how much it would cost to go to Sucre, and they told him 200 Bolivianos per car, a third more than it usually is but still acceptable. They took us to the blockade line and there the road was blocked off by several large trucks so we doubled back and turned off the main road to an extremely rough and rocky dirt road that wound through the poorer parts of Potosi before descending down past the silver smelting plant and rejoined the main road in sight of the other side of the blockade. As he was negotiating this road our driver was on the radio with taxi headquarters and they were constantly asking if it was possible to get past the blockade, he kept saying maybe but that road was really ugly; I´m pretty sure he destroyed the car’s shocks getting us past the blockade.

Two hours later over some very empty and well-paved roads we reached the frontline of the Sucre blockade and we could go no further. The six of us piled out of the cabs and snaked our way through the maze of angled buses and trucks that were blocking the road, for maybe a kilometer or so before we made it to the other side. Luckily on the other side a taxi was waiting and he said he would take us into the center for 10 Bolivianos, that sounded good so got into the cab and about 15 minutes later we were at our hostel. Then all of sudden the driver told us it was going to be 10 Bolivianos per person. We started arguing with him and traffic police came over, because we were blocking the road and making a scene, and even he agreed that 10 Bolivianos per person was way too much and told the taxi driver to go down in price, which he did to 8Bs per person. That still seemed way too much for us so we gave him 30 Bs total and refused to give him more. Eventually he left in a swearing huff. It was an ordeal but Sucre seemed like a much more welcoming place than Potosi, except for this taxi driver.